This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Research

Revealing Alzheimer’s hidden clues

Taking methods developed by astronomers to discover distant galaxies and adapting them to image the eye, CERA researchers are revealing hidden signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is the leading cause of dementia and is the third leading cause of death in Australia.

Despite decades of research, progress towards treatments for Alzheimer’s disease has been lacking – until recently – as CERA Deputy Director Associate Professor Peter van Wijngaarden explains.

“There are two medications that show promise in slowing memory loss in Alzheimer’s disease, something that was almost unthinkable even just a few years ago.”

While it is exciting news that people with Alzheimer’s disease may soon have treatment options, by the time most are diagnosed, they have already suffered irreversible brain damage.

“The earliest changes in the brain occur 20 to 30 years before memory impairment, so there is a huge window of opportunity to detect people at risk of the disease at its early stages so treatment can be started when it is most likely to be effective,” says Associate Professor van Wijngaarden.

Tests that are currently available to detect the earliest signs of Alzheimer’s disease – the collection and testing of spinal fluid, or highly specialised brain scans – are invasive, expensive and not widely available.

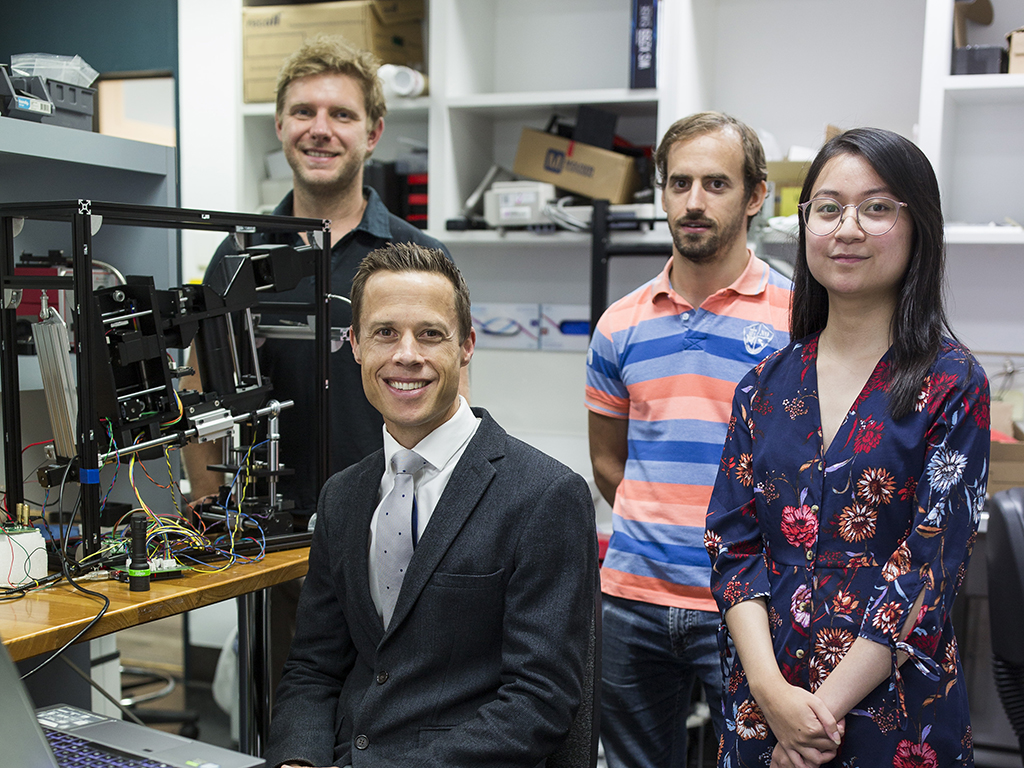

Associate Professor van Wijngaarden and his multidisciplinary team of scientists, engineers and mathematicians have developed a new camera to detect signs of Alzheimer’s disease in the eye.

“We can acquire a retinal image in a quarter of a second, without using drops to dilate pupils,” he says.

“Our scanning technology is similar to a standard eye photograph, but instead of using a standard flash of light, we use a rainbow-coloured flash.”

By looking at the way that light of different colours is reflected from the retina, the team can see signs of Alzheimer’s disease that cannot be detected with traditional imaging approaches.

“Just as astronomers can learn new things about distant galaxies by using a range of telescopes that are sensitive to different colours or wavelengths of light, we can learn new things about the retina with our camera,” says Associate Professor van Wijngaarden.

Spotting early signs

Associate Professor van Wijngaarden’s team is looking into the back of the eye to the light-sensitive retina for biomarkers – signs that indicate whether a person may develop a particular disease, or how likely existing disease might be to progress.

In Alzheimer’s disease, the main biomarker is a waste product produced by the brain – a type of protein called amyloid beta.

There have recently been innovations in identifying retinal and blood biomarkers, with blood tests that can provide information about levels of proteins cleared from the brain.

Associate Professor van Wijngaarden believes blood tests and hyperspectral imaging may be used as complementary diagnostic tools.

“We know the Alzheimer’s disease process affects the retina, and hyperspectral imaging allows us to look at directly affected nerve tissue.”

The hyperspectral camera developed by the CERA team takes an image using 30 different colours of light.

“By sequentially imaging with different colours of light, we obtain far richer information about the structure of the retina than would otherwise be the case,” says Associate Professor van Wijngaarden.

This rich image data is then processed using artificial intelligence, to predict who is at risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

Future of eye tests

“Hyperspectral imaging is a new way of looking at the retina,” says Associate Professor van Wijngaarden.

“Every disease we’ve looked at using hyperspectral imaging, including glaucoma, diabetes and now age-related macular degeneration, we’re seeing unique things can’t be seen with other imaging types.

“A lot of the fundamental discoveries we’ve made using this technology have been with the support of the H&L Hecht Trust and the Yulgilbar Alzheimer’s Clinical Research Program.

“And our collaboration with the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle Study of Aging, has been essential for recruiting study participants.”

The team aims to make hyperspectral imaging available in every optometry and ophthalmology clinic for improved detection of Alzheimer’s disease as well as a range of sight-threatening eye diseases.