This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Stories

Dr Graeme Pollock OAM: a remarkable legacy

After 32 years pioneering and advancing corneal transplantation at the Lions Eye Donation Service, Dr Graeme Pollock OAM is taking his next big step.

As his retirement day nears, the Lions Eye Donation Service (LEDS) Director Dr Graeme Pollock OAM says he still remembers the exact date he started.

“March 11, 1991.” And he has been at the helm since.

The seed for the eye bank was first planted in the mid-1980s when District Governor of Lions Club Victoria Leo Tyquin asked his ophthalmologist Dr Ian Robertson OAM, then Head of the Corneal Clinic at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, what was needed to improve sight in Victoria.

His response: “an eye bank”.

“LEDS essentially wouldn’t exist without Lions,” says Dr Pollock.

From 1991, LEDS was embedded in the University of Melbourne’s Department of Ophthalmology at the Eye and Ear Hospital, headed by Melbourne Laureate Professor Hugh R Taylor AC, who would go on to establish CERA in 1996.

“Professor Taylor is a giant in stature and reputation, and had an enormous influence on everything I did,” says Dr Pollock.

Dr Pollock says LEDS’ philosophy was formed early on when he presented David Welsh, then Lions Management Committee Chair, with two options for a device he needed for his lab.

“David looked at them and said: ‘Graeme, one is more economical, but which one’s the best?’

“That really stuck with me and still runs through LEDS today: We don’t aim to be the biggest, but we always aim to be the best.”

At last count, LEDS had saved the sight of almost 15,000 people in need of corneal transplant surgeries — “20,000 if you include sclera,” says Dr Pollock.

Early career

From the moment he graduated from the University of Melbourne, Dr Pollock immersed himself in the world of organ donation research.

He started in Brisbane as an assistant researcher in kidney and liver donation, going on to complete a PhD in transplant research – also spending time at the University of Cambridge.

Cambridge proved an excellent training ground for Dr Pollock’s future role, where he was a research assistant in a department headed by organ transplantation pioneer Sir Roy Yorke Calne and had his PhD examined by future UK Eye Bank leader Professor John Armitage.

As a research assistant, Dr Pollock also took part in emergency organ donor retrievals, which involved flying out in the middle of the night to Germany.

“One time I thought of my uncle, who was in the Airforce during World War II and disappeared over the North Sea,” he says.

“Only one generation later, I’m flying over the North Sea at 2am to retrieve donor organs.”

In early 1991, Dr Pollock saw an advertisement to set up an eye bank at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital and moved home to Melbourne.

“I thought, ‘I could have a crack at doing that’. And I’ve been here ever since.”

A better system

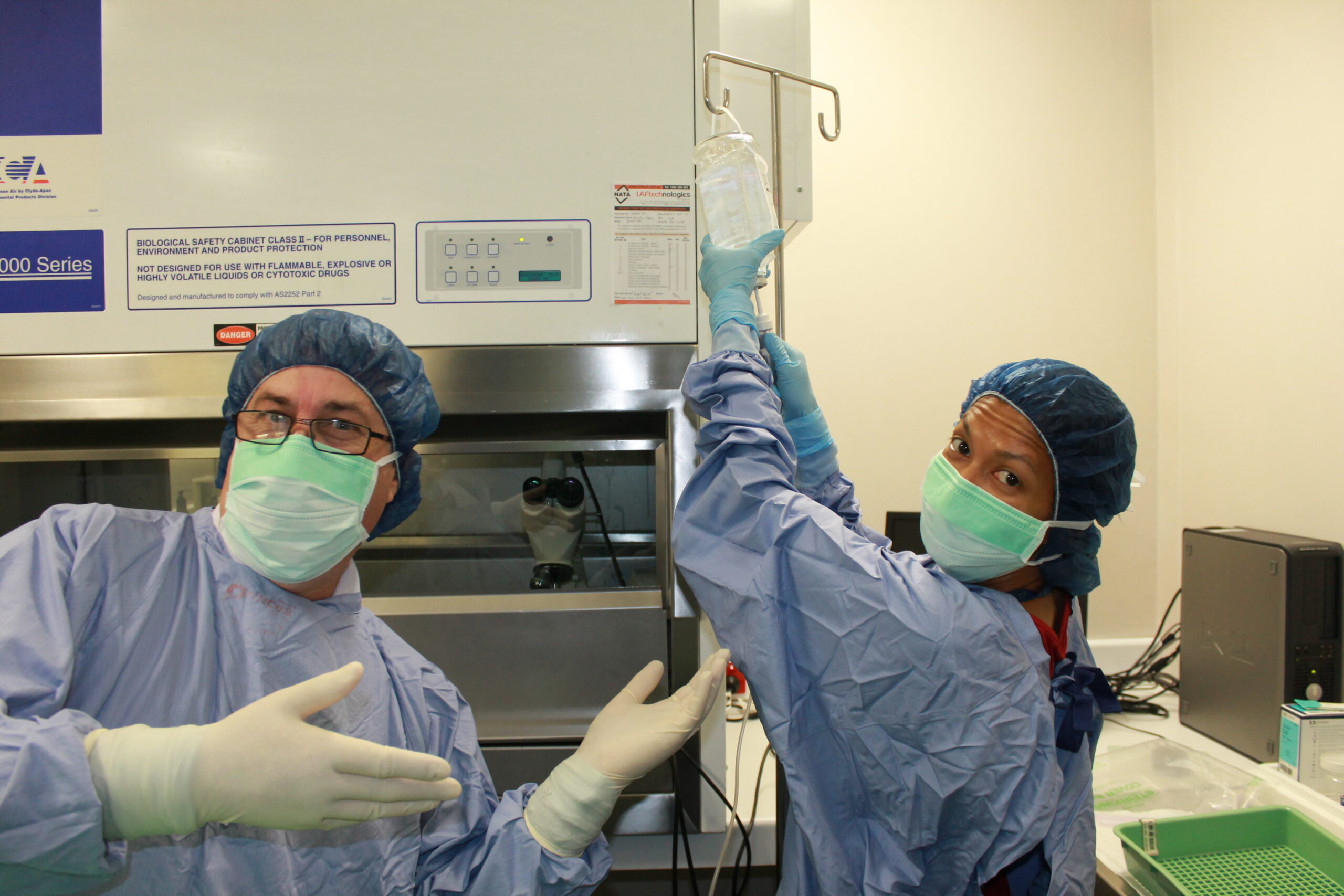

Dr Pollock and his team of eye tissue experts have been at the forefront of innovation.

Not long after LEDS was established, the hospital provided Dr Pollock with a waiting list that had over 400 people – some having waited over three years for a transplant.

When Dr Pollock realised LEDS were preparing enough corneas on a weekly basis, he moved towards scheduled corneal transplant surgeries – an Australian first that greatly reduced waiting lists.

“Within six months, the hospital went from 95 per cent of transplants being done after hours to less than five per cent,” he says.

“There’s the satisfaction not only helping give people sight but also knowing you’ve started a better system.”

Their pioneering use of specular microscopy, which allows eye tissue coordinators to determine a cornea’s viability for transplant, also helped eliminate long waiting lists.

“Before specular microscopy, the donor age was limited to around 65 because, beyond that age, you couldn’t be sure of the cornea’s viability,” says Dr Pollock.

Suddenly, donor age went up to 85 and LEDS reached a point where they had an excess of donor tissue and are now the largest exporter of corneas to New Zealand.

We never close

During LEDS’ first decade, Dr Pollock worked as both director and often around the clock as one of two eye tissue coordinators.

“To this day, whether it’s three o’clock in the morning or Christmas day, there is always someone on call,” he says.

This involved gaining consent from donor families and going out medical facilities around the state to retrieve eye tissue, preparing it for surgery and finally delivering it to the destination hospital – all within a matter of hours.

“You quickly develop skills as a jack of all trades: including social worker, nurse and medico,” he says.

While he started as a researcher, Dr Pollock says he didn’t really get career satisfaction until working at LEDS.

“The first week the LEDS opened, I had a thank you from a donor family, the ophthalmologist and a recipient.”

He also became mentor to Dr Prema Finn when she joined LEDS in 2000 in her first role as a donor coordinator.

“Going out to the first donor family with Graeme was, pardon the expression, an eye opener – seeing his respect for the donor and empathy for the family,” she says.

“I often wondered whether I could ever do my role as well as him. After 20 years, I’m a little bit closer.”

Advancing eye banking globally

During the 2000s, Dr Pollock says there were many advances in eye-banking both at LEDS and overseas.

“In my travels, I found European and American Eye Bank societies had great skills in specific areas, but they didn’t communicate and share knowledge.

“I thought there must be a way to get eye bankers to network better.”

Bringing together representatives from around the world, he established the Global Alliance of Eye Bank Associations (GAEBA), which continues to support and advance eye banking.

Advancing corneal surgery

In 2005, LEDS moved to a purpose-built laboratory and was the first eye bank in Australia to adopt organ culture preservation, which keeps eye tissue in an incubator at body temperature.

Dr Pollock says corneas went from lasting seven days last up to 30 days: “This changed how we did everything at the eye bank.”

In following years, eye banks around Australia would also adopt this technique.

This paved the way for LEDS to study pioneering new techniques such as pre-cutting of corneas for partial corneal transplants, where the surgeon only replaces the diseased layer of tissue.

“Graeme pioneered ready-made, bespoke corneas for surgeons,” says Dr Finn.

“I initially predicted we’d do 20 pre-cut corneas per year, and it’s about 70 percent – or about 400 – of what we now do,” says Dr Pollock.

Advances in pre-cutting techniques in the last decade mean that LEDS can now cut an even thinner microscopic layer of tissue – essentially just the rear layer of the cornea.

“Until last year, we were the only eye bank in Australia that did that,” says Dr Pollock.

“I think we’re going to see this technique used much more into the future.”

Safe hands

Dr Pollock says people sometimes ask why he’s worked in the same job all these years.

“I tell them ‘It might be the same position, but it’s never the same job’.

“Looking back, it’s remarkable to see the growth and change of practice – and I’m leaving behind a team with the best expertise in the world.”

In 2018, Dr Pollock’s career long dedication to advancing corneal research was recognised when he was made a member of the Order of Australia (OAM).

And capping off a distinguished career, he was presented with the Victorian Lions Foundation Leo Tyquin Award at his farewell to recognise his 33-year mission to advance eye banking.

CERA Managing Director Professor Keith Martin says CERA is incredibly grateful to have had Dr Pollock at the helm of LEDS.

“Graeme has done an enormous amount of work to transform corneal transplantation in Australia and around the world,” he says.

“His leadership, expertise and passion for what he does has been truly inspiring.”

“My time”

Dr Pollock is looking forward to retirement.

“There’s the sudden realisation that, for the first time in many years, the only people I’m responsible for is my wife and myself – which in a way is an enormous relief,” he says.

Retirement will also give Dr Pollock more time to spend with his daughter and two sons, with his youngest son dividing his time between being a vet in Manchester and travelling the world.

“I’ve lost count of the countries he’s visited. We’re meeting him in Iceland soon because he’s already been there and recommended it,” he says.

“It’s a bit of a cliché you hear from retirees, but I’ve come to realise this is my time.”